Refugee-Refugee Solidarity in Death and Dying

Exhibited as part of the 2017 Venice Biennale, Dr Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh (Refugee Hosts’ PI) and Yousif M. Qasmiyeh (Refugee Hosts’ Writer in Residence) were commissioned to co-author this photo-essay for the Tunisian Pavillion’s exhibition space, The Absence of Paths. You can see the original publication on The Absence of Paths here, and read Yousif’s poem, ‘In arrival, feet flutter like dying birds’ (also exhibited as part of the 2017 Biennale) here.

by Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, UCL and Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, University of Oxford

Baddawi is an urban Palestinian refugee camp on the outskirts of Tripoli in North Lebanon. Born in the 1950s, the camp has been home to ‘established’ Palestinians and their descendants since then, and to other refugees displaced within and beyond Lebanon. These include, most recently, refugees fleeing Syria: Syrians, Kurds, and Palestinian and Iraqi refugees formerly based in Syria.

This reflection, and the photographs that accompany it, are part of a 4-year research project funded by the UK’s AHRC and ESRC examining diverse spaces of encounter between refugees from Syria and host communities in camps and cities across Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. In the context of an overwhelming focus on tensions and/or acts of hospitality between the living, here we shift our attention to solidarity in death and dying, with the cemetery taking centre stage for both the living and dead, becoming the camp’s only fixity. Different refugees enter the camp, with the camp becoming both a gathering and a gatherer. The cemetery, too, echoes this duality.

Which is older: the camp or the cemetery?

At the core of Baddawi refugee camp, from its very birth, the cemetery has hosted the living and the dead. The arrival of the living to the camp, was traced by the arrival of the dead. From that core, the camp has grown, and so too have its residents. As time has passed, and as wars have led to new arrivals – Palestinians from other camps, Syrians, Kurds, Iraqis… – , the cemetery has outgrown its original space. The camp is denser, higher, narrower. And a second, a third,… now a fifth cemetery in Baddawi, for Baddawi and beyond.

At the historical, physical and metaphorical core of Baddawi camp is the original cemetery, which continues to host the camp’s ‘original’ residents. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016

As he digs, the name digs with him. The shovel of noise is the name.

Abu Diab, the only grave-digger in the camp, works ceaselessly: two days to dig one grave.

Sensing the arrival of death, he enters the newest cemetery and starts the preparations. The graves are shallower now. Half as deep, for a population that doubles with each war. He speaks of the pragmatics of dying: “I dig for the living, and I dig for the dead.” To live and maintain life, to keep the dignity of the dead and the solace of those who remain.

Abu Diab’s hands at rest. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016.]

They die, they say, so they remain.

The place is never theirs. Nor is the name.

Determining a place consists in determining the death of its people at the same time.

Those refugees who left the camp in life return in death: a sense of belonging to that land, ‘a’ land that is ‘theirs’ even if ‘their’ land remains elsewhere. Those who live on the borders of the camp –whose citizenship does not afford them the riches to be buried in a citizen-grave – arrive in a space that is not theirs. Now, the shared spaces have become denser, with the camp and its cemeteries welcoming the living, dying, and the dead who originated elsewhere (at some time, always-already in the middle of time).

The camp’s thresholds continue to expand, blurring the beginning and end of the cemetery and the houses surrounding it. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016.]

The tombstone, to a certain extent, to the extent of the farthest extent,

is what the dead cannot see but sense.

The name is high, but whose name is it that is in the grave?

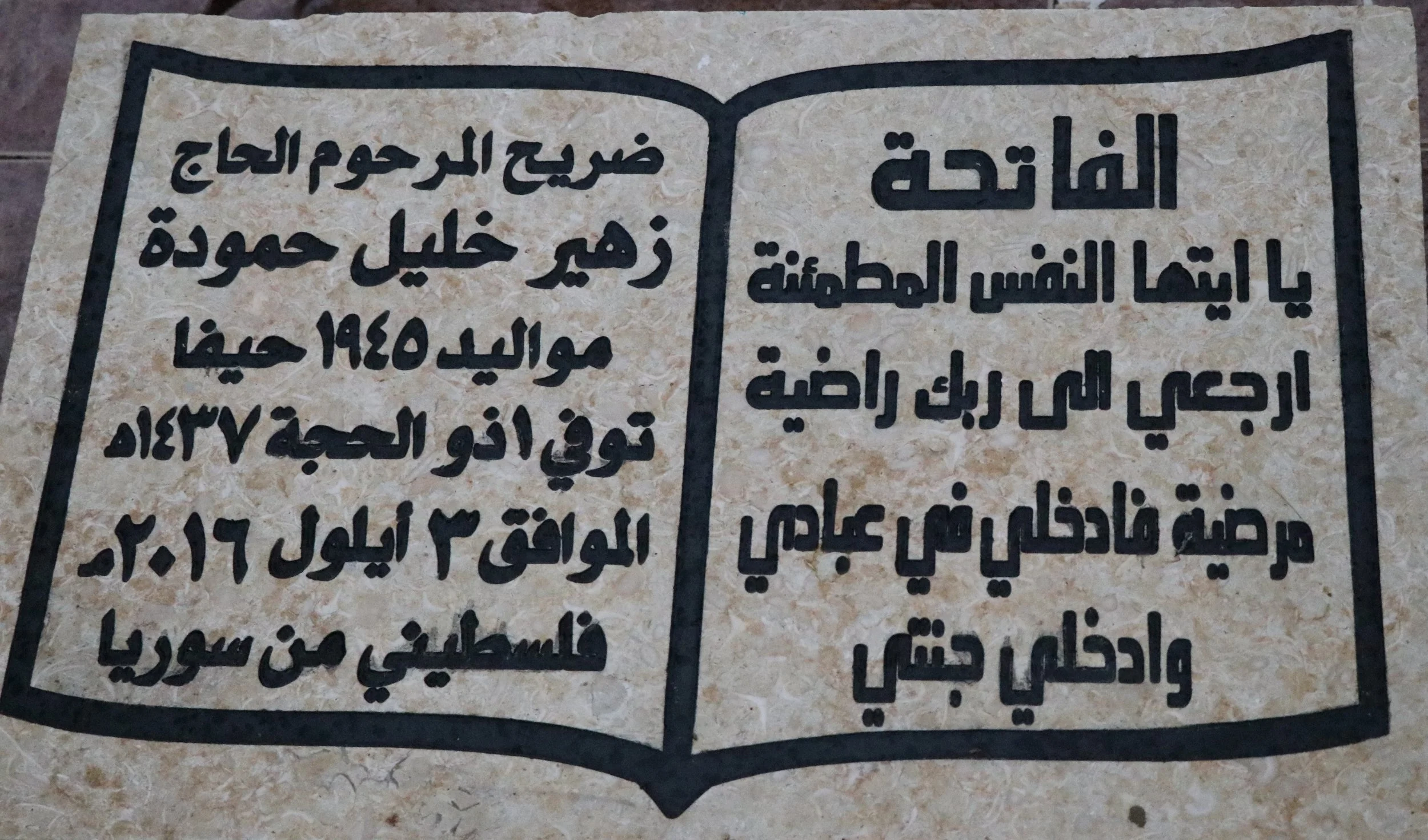

The tombstones of the newest cemetery – now full, now no longer the newest – now mark names, dates and places of origin that trace the longest journeys: “Born in Haifa in 1945… died in Baddawi in July 2016… Palestinian from Syria…” The words of – and over – the dead mark the multiple states of refugeeness, the past, and the place.

This tombstone, marking a grave in the camp’s fifth cemetery, offers testament to the contours of a journey which has come to an end in this space. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. January 2017.

It is not a right to bury yourself amidst those people, in the graves that they never own, but it is the right that has failed to become a right on its own, on its naked own, so it would self-dilapidate until all resurrects.

The tombstone is the concrete identifier of origins.

From Syria, new arrivals have descended into Baddawi: Syrians, Palestinians, Iraqis and Kurds are all now sharing the same soil.

In Baddawi camp’s fifth cemetery, graves continue to be marked by life. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. January 2017.

When he died, an orchard of dialects grew on the tongue.

As the newest cemetery is being born on the periphery of the camp, green as the buds emerging from the newly dug mounds, the original cemetery remains at the core.

The cemetery is one of the only ‘open spaces’ in the camp, and is – and always has been – an important space for children to play. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016.

Children playing in the original cemetery in Baddawi refugee camp. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016

Since everything overlooks a cemetery,

it is the cemetery that is a camp more than the camp itself.

The camp never dies. It is its own God.

On land, the cemetery is marked by concrete and children playing in its grounds, and from the sky, by the moon shining over Masjid al-Quds.

Masjid al-Quds – in the background – overlooks the cemetery, the camp’s ultimate shared space in life and death for new and established refugees. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. July 2016.

You can read the original version of this photo-essay on The Absence of Paths here, and read Yousif’s poem, ‘In arrival, feet flutter like dying birds’ (also exhibited as part of the 2017 Biennale) here. This piece was originally posted on Refugee Hosts.

![Abu Diab’s hands at rest. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5748678dcf80a1ffcaf26975/1498807527219-DMQLB4UQJE7Q6URNGFSM/image-asset.jpeg)

![The camp’s thresholds continue to expand, blurring the beginning and end of the cemetery and the houses surrounding it. (c) E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh. December 2016.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5748678dcf80a1ffcaf26975/1498807670565-41IZKJI9O2F1594UERLD/image-asset.jpeg)