A new politics of solidarity?

Over the past five years, tens of thousands of ‘ordinary people’ have undertaken voluntary work in support of, and in solidarity with, forced migrants in Europe. The New Internationalists: Activist Volunteers in the European Refugee Crisis aims to capture the scale and diversity of this international activist movement, lauded as one of the largest in European history. The book foregrounds the testimonial accounts of those volunteers who, with little to no training or support, worked to provide emergency aid, conduct sea rescues, develop community support structures, organise protests and advocacy campaigns and launch legal challenges with and on behalf of displaced people.

Edited by Sue Clayton, The New Internationalists aims ‘to reverse the gaze that the Western world turned on refugees, to investigate instead our own responsibilities in a Europe that has chosen to close its borders’ (3). It forms part of a growing body of research concerned with documenting the grassroots movement that emerged in response to the so-called ‘refugee crisis’.[i] This research scrutinises the failures of UNHCR and the traditional humanitarian sector to coordinate an adequate response to the events of 2015-16. It also criticises the politics of deterrence and ‘violent inaction’ employed by EU states to prevent and discourage irregular border crossing.

This recent research into the ‘volunteer phenomenon’ also aims to define and dissect the essential characteristics of the grassroots activist movement: its self-identity and values, its strengths and limitations, its relationships with governments and NGOs, its impact (both intentional and unintentional), and its future in the face of the criminalisation of refugee solidarity. To this burgeoning sub-sector of humanitarian research, The New Internationalists contributes an experimental, holistic and pan-European account of the grassroots voluntary movement. It argues convincingly that these activist volunteers, while not a homogeneous group, witnessed the ‘crisis’ from a unique vantage point due to their proximity to and sustained communication with displaced people travelling through Europe, and thus share a certain knowledge which exceeds that of both European governments and the media.

The ‘Refugee Crisis’: A Topological History

The New Internationalists combines three distinct styles. Theoretical arguments are interwoven with short journalistic summaries of ‘key flashpoint locations’ across Europe, and the testimonial accounts of around 60 grassroots volunteers.[ii] In style and structure, The New Internationalists resembles the volunteer effort itself: a little fragmented, but inventive, offering up raw insights that a more traditional approach may well have overlooked or dismissed. The opening chapters provide statistic-heavy summaries of who sought asylum in Europe, for what reasons and in what numbers. John Borton offers a general overview of how the humanitarian sector’s ‘shockingly inadequate and unsatisfactory’ (29) response led to the emergence of more than 180 grassroots volunteer groups across Europe.

The second and largest section of The New Internationalists is structured as ‘a kind of topological history’ (11), combining journalistic ‘flashpoints’ with volunteers’ testimonial narratives in a way that approximates the journeys taken by displaced people across Europe. The narrative begins in Southern Europe with the Greek Islands (Lesvos, Chios and Samos) and the Central Mediterranean (Lampedusa, Sicily and Malta). It travels through the Balkans and to the internal border zones of Idomeni and Ventimiglia, then north again to Calais, Dunkerque and Brussels. The journey ends at some of Europe’s ‘destination points’: the UK, Paris and Athens.

Some of the testimonies included in the book, particularly those written by volunteers working on rescue ships, are uncompromisingly graphic and horrific to read, especially in quick succession. Indeed, Clayton voices her reservations about publishing the most extreme of these testimonies, fearing that ‘the graphic detail somehow objectifies people who have died, and disrespects them.’ In the end, however, she concludes that ‘the very least we must surely do is bear witness to this reality’ (112).

The European tour of volunteer testimonies is bookended by theoretical reflections upon the political, personal and psychological implications of the activist volunteer movement. Justine Corrine, Charlotte Burck and Gillian Hughes describe the mental health challenges experienced by volunteers in Greece and Northern France. They explain how inexperience, a culture of overwork and a lack of official support structures meant volunteers’ mental welfare proved a serious challenge for grassroots groups, and one that they are yet to overcome. These practitioners suggest that, in the future, psychological ‘support for volunteer activists in Europe needs to be built into organisational structures and whole communities’ (296).

Finally, Anna-Louise Milne asks whether the activist volunteer movement represents a ‘new politics of solidarity’ in Europe. She usefully tempers claims that this volunteer phenomenon was entirely unprecedented by placing it within longer histories of activism, including the sans-papiers movement in France. Today, Milne argues, the relationship between humanitarianism and politics has shifted as a result of the criminalisation of solidarity. Where humanitarian acts and political acts overlap, ‘new patterns of political practice’ (375) are beginning to emerge. The New Internationalists ends by bringing us into the present, exploring the additional challenges that Covid-19 has posed to sea rescues and to expressions of political and community solidarity.

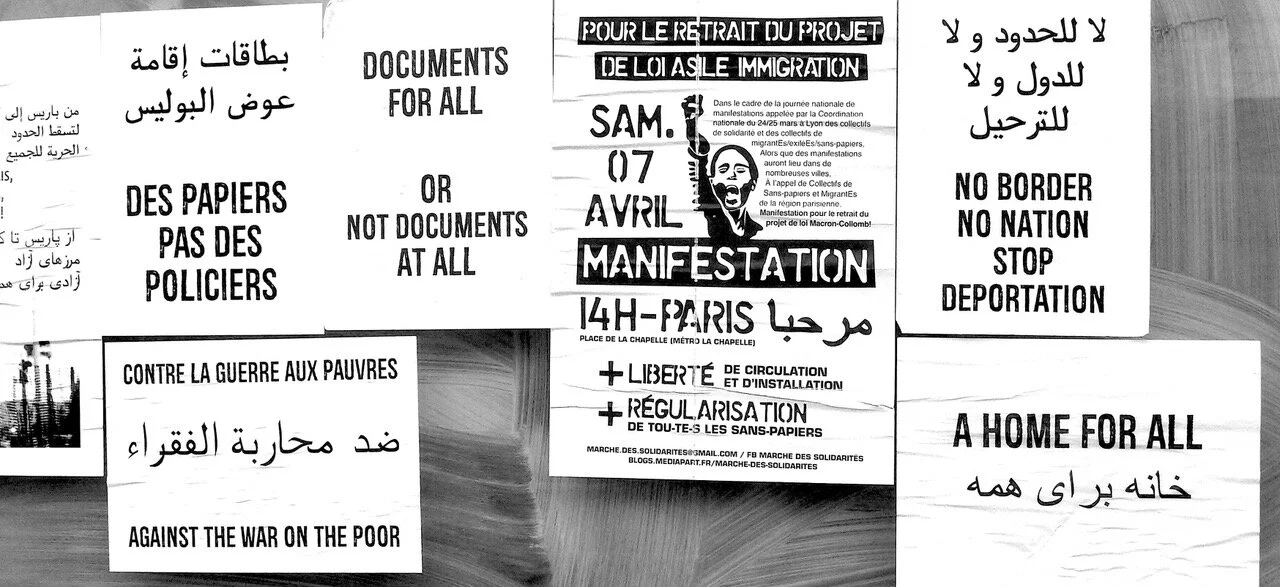

Paris, France, 2018. Political posters in La Chapelle district (in French, Arabic and English) protest against the law restricting procedures for claiming asylum. Image credit: Anna-Louise Milne / The New Internationalists

Humanitarianism: To Redefine or to Replace?

If we accept, as this book does, that the ‘roles played by volunteers have re-drawn the map of civic responsibility and citizenship’ (2), then the question we are left with concerns the borders of humanitarianism itself. Does this new grassroots movement view ‘humanitarianism’ as a dominant power to be resisted, or as something that can adapt to the new futures of refugee aid and solidarity? Does this movement seek to redefine traditional structures of humanitarianism, or to replace them, leaving established NGOs by the wayside as outdated and overburdened models? In either case, a basic tenet of the grassroots activist movement has always been its commitment and capacity to learn from the mistakes and limitations of traditional humanitarian approaches.

For this reason, The New Internationalists may have missed an opportunity to reimagine more fully the visual culture of forced migration alongside the practical response. The book contains over a hundred photographs, which provide a visual narrative of the ‘crisis’. Some of these images reproduce classic visual tropes of refugee humanitarianism: anonymous figures queueing for aid, crammed into dinghies and wrapped in emergency blankets. One might expect this new form of citizen solidarity to be more ambitious in rethinking the visual language of forced migration, and to move more decisively away from stereotypical ‘humanitarian’ images of refugees as disempowered, helpless victims.

During the book launch for The New Internationalists, contributing author Nidžara Ahmetašević reminded us that the border separating present conditions of displacement from the supposedly discrete category of ‘refugee history’ is constantly being revised and redrawn. She explained how, in the Balkan states, multiple ongoing histories of forced migration overlap and intersect in complex and unpredictable ways, as those formerly displaced by the wars of the 1990s provide support and solidarity to Europe’s new arrivals today, despite their own exclusion from the geographical and political area of the European Union. Through its patchwork narrative, The New Internationalists gives us a sense of this unstable and shifting threshold of refugee history, capturing the parallel moment at which the ‘refugee crisis’ became part of history, while at the same time remaining an irreducible part of our present reality.

[i] These are questions that have been explored in previous Refugee History posts by Tess Berry-Hart and Elisa Sandri.

[ii] These 60 testimonies represent part of the archive of over 170 testimonies collected by the editors, which will be available in full in the e-book.

The header image shows solidarity campaigners in Paris, France, 2018: in front of the Sacré Coeur basilica, they have hung a banner reading (in French) 'Unconditional Welcome for All Exiled People'. Image credit: Accueil de Merde / The New Internationalists.