Digital research on twentieth-century refugees: dealing with information overload

Digital technology has transformed archival research. Instead of painstakingly taking notes most historians today take digital pictures or scans from archival documents. The advantages are undeniable: it reduces time spent in one archive, which increases the possibility to visit more archives and enhances accuracy. However, there are downsides, too. Access can lead to excess. The sheer volume of paper has exponentially increased since the invention of the typewriter in the late nineteenth century; computers, digitisation, and online access have only enhanced this growth. Hence, historians often end up with enormous collections of research photos on their personal devices. Many struggle to properly process their digital material. The problem of multitude is no longer situated during but after the archival visit.

The struggle became real in my own research on international refugee policy in the 1970s – the era when computerized telegrams were introduced. For my PhD project on the international resettlement of Ugandan Asians in 1972, the Chileans in 1973, and the Vietnamese between 1975 and 1979, I collected approximately 100,000 digital documents from both physical archives (approximately twenty archives across eight countries on five continents) and digital ones (mostly the American State Department’s Access to Archival Database or AAD). Here, I share my experiences of dealing with such abundant and diverse information and the opportunities for historians offered by ‘distant reading’ techniques.

Digital research methods, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP), can provide solutions for large corpora, but they require digitised material with high accuracy. Most digital historical research therefore deals with sources that are ‘born digitally’ (such as the electronic telegrams in AAD) or with crowd-sourced data that are manually inserted into digital databases. I needed to combine information from digitally born sources (20%) with a large corpus of typewritten (>75%) and handwritten (<5%) sources. Manual transcription into a database was only possible for the handwritten files; the typewritten corpus was simply too large. Moreover, the quality of the typewritten material varied starkly, from good to barely readable. The challenge was to deal with this information overload through a hybrid digital method, which could enhance the analysis without major distortions caused by the internal diversity of the material.

Together with an interdisciplinary team, I designed a three-step method based on augmented intelligence. We used digital methods to analyse the files, while ‘keeping the historian in the loop’. Every step was thus verified and tested against historical knowledge acquired by more traditional research methods, such as close reading and discourse analysis.

Step 1: Digitising documents

Optical Character Recognition (OCR), a technique used to convert analogue to digitised text, has improved markedly, but research shows that a threshold of 80% correctly recognised characters is necessary for digital analysis. The variation of the typewritten sources (due to low quality paper, ink, preservation, etc.) affected my corpus enormously. Some archives – particularly the archives of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Geneva – showed considerably poorer results of OCR quality (<80%), while others, mostly the national archives of the UK, US, Vietnam, Chile and Uganda, had high degrees of consistency and quality (>90%). But what effect did this have on our analysis?

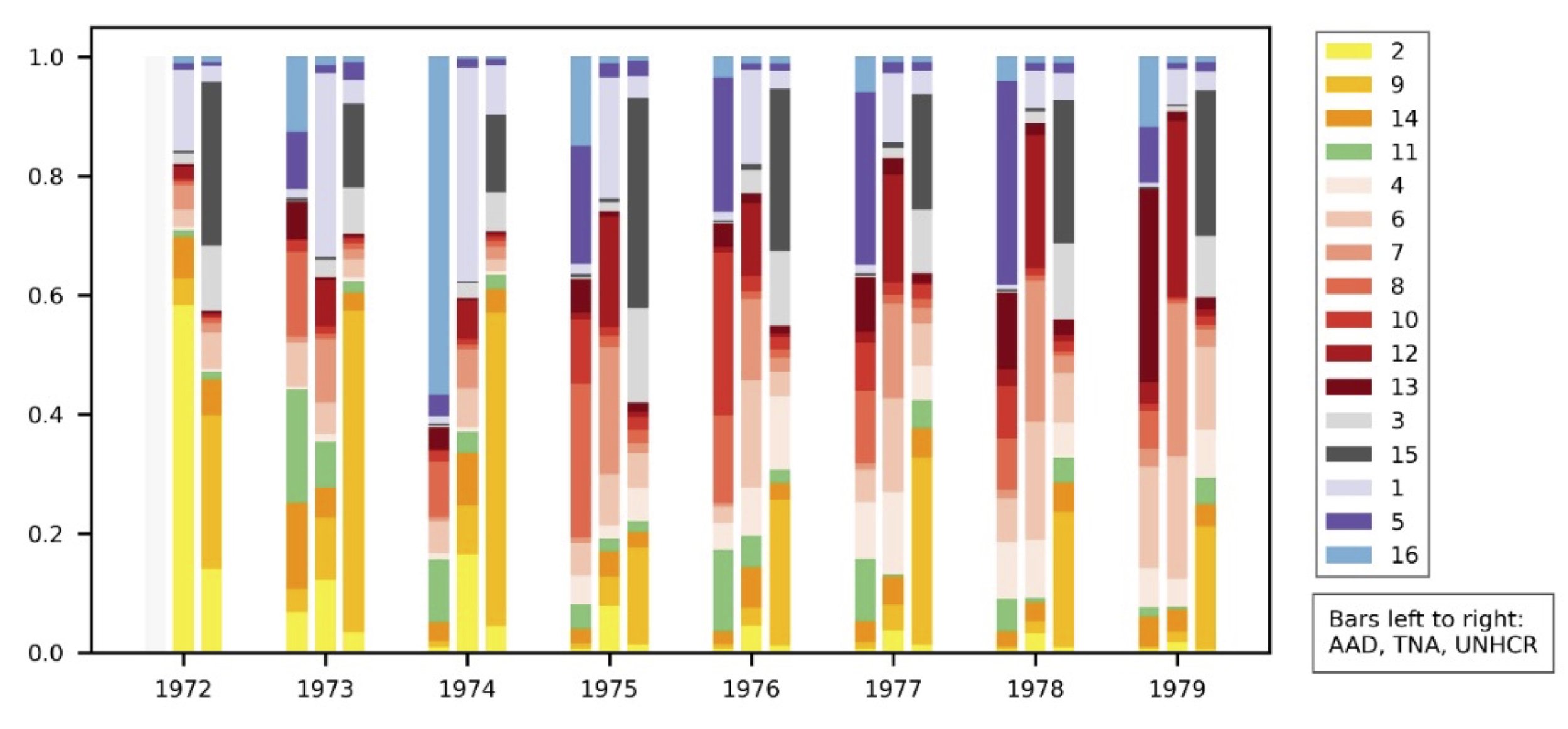

To verify whether the digitised material was useable for digital research, we compared the OCR text with the digitally born telegrams from the American State Department. We selected a test sample including 4,679 records from the UNHCR Archives in Geneva, 7,272 records from the British National Archives, and 8,646 electronic cables from AAD, all in English. We then used topic modelling to compare the results between the three collections. We found that the computer was able to distinguish between various themes within the archives related to the research question, focusing on the resettlement of the Ugandan Asians, Chileans, and Vietnamese between 1972 and 1979. For each group, the computer could identify one or more topics. It also identified four topics related to policy making (two related to UNHCR, and one each to the UK and US policies). A last topic isolated all documents unrelated to resettlement that were inserted by mistake (see graph). This division occurred automatically, without human intervention, and thus showed that the computer correctly understood the input. Moreover, we found that the computer identified the same themes (‘topics’) across all archives, both in the digital and the typewritten sources and regardless the OCR-quality. This result indicated that all collections were suitable for digital analysis.

Visualisation of the topics per year and per archive (AAD = American electronic cables, TNA = British National Archives, UNHCR = UNHCR Archives). The yellow topics relate to the Ugandan Asian casus, the green to Chile, the red to Vietnam, the grey to UNHCR policy, the purple to British and American policies; blue indicates the anomaly of the mistakenly inserted data.

Step 2: Hypothesis formation

Historians have the appropriate disciplinary knowledge to judge the quality of results derived by technology, but they also come to their research with preconceived notions and biases, which can blind them to other results and outcomes than they had in mind. We combined technological solutions with interdisciplinary communication and iteration to come to a model that can supplement and support data exploration and hypothesis formation. While the backbone of this research has a solid historiographical-theoretical underpinning and thorough understanding of the data through close reading, distant reading can be used to point historians in new directions, especially when the potential corpus of sources is larger than a single researcher can read in a lifetime.

We used another Natural Language Processing method, namely clustering, to find how the topics related to each other. One key finding was the centrality of human rights, most particular the right to freedom of movement, in policy discussions regarding refugee resettlement. These debates occurred in relation to the freedom of movement of Ugandan Asians towards their former imperial metropole, the UK, but the topics also showed how this discussion surfaced in the subsequent resettlement periods. This result was unexpected and led to new research questions.

Step 3: Analysis

The output of our method was a ‘reading list’ of the most important pages per topic. Instead of starting the daunting task of combing through approximately 100,000 documents in an unstructured way, my reading method became highly structured. I used the pages in the reading list to detect interesting lemmas for further full-text search and explored the material, including sources in other languages than English, through traditional complementary methods.

Digital methods can help in managing the overload of digital sources historians currently face. They can gauge the quality of the digitisation before one delves into the material. And they can reveal patterns potentially undiscernible for a human reader. However, these solutions are not value neutral. They still reflect the heuristic process of the researcher, and the inherent biases, gatekeeping and colonial legacies within the archives. Moreover, digital technologies, often engineered to perform best in an English-language environment, add their own biases to the process. Therefore, we opted for augmented rather than artificial intelligence. By pointing to interesting areas for close reading, while all interpretation and mistakes remain the historians’ responsibility, the computer supports but does not take over the analysis from the historian.

*

This digital research project was partly funded by the Research Foundation – Flanders (Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, FWO). Sara Cosemans is grateful to her interdisciplinary team, without whom she would have never managed to conduct the digital analysis. She also wants to thank the editors of RefugeeHistory.org for their helpful suggestions and Evan Smith for the meme.

The header image is adapted from a Tintin comic by Hergé. A haggard-looking Captain Haddock leans at the bar saying “What [an archival visit], huh?” Tintin, next to him, says “Captain, [that’s just taking the photos]”. © Evan Smith, Flinders University