Waves of migration: a Vietnamese refugee boat journey in numerical modelling and oral history

The journeys of people who have been forced to leave their homes have, over centuries, included travel across water, including rivers, oceans, and seas. Such journeys have come into public view in a range of ways and for different reasons. It may be through news reports of boats sinking, where many people drown. Or it may be through the actions of governments and non-governmental organisations to manage the movement of people, humanitarian and activist groups that rescue people at sea, and individuals documenting their own journeys of escape.

Humanities-based research has reflected upon how refugee boat journeys are represented, the narratives and discourses develop around these journeys, and the impact of these lived experiences of forced displacement upon individuals and intergenerationally. Critical ocean studies has demonstrated the significance of learning from Indigenous knowledge and feminist scholarship to consider how geopolitics is connected to the fluidity and flows of the sea.

In a recent article we have taken a different approach to researching refugee boat journeys by sea, based on a collaboration between historians and ocean engineers. We have used oral history research alongside numerical modelling connected to a particular boat, so that the sea state the boat travelled through and the specific movement of the boat in those conditions could be determined. Through working in an interdisciplinary way, we have sought to expand the sources we might use to write histories and the types of data that can help us to understand events in the past. In this work we saw the development of a scientific narrative that was read alongside an oral and community history of Vietnamese refugee survivors, in order to theorise the ocean as an active agent in a refugee boat journey. The scientific analysis explains how the ocean and weather, paradoxically, both created the conditions that were dangerous for this vessel, but also placed it in a position where it was rescued.

Anh Nguyen Austen, one of the historians working on this project, was on the boat. She was a child at the time and a member of an extended family group who, wanting to escape Vietnam with their children, left on the vessel which was disguised as a fishing boat. The boat was to head east towards the Philippines, where they hoped they would be rescued by a commercial ship. It was approximately 10m long and 2.5m wide, and built to carry no more than 40 passengers, but during the process of embarking under the cover of darkness, many more people boarded the vessel.

The boat’s engine failed when they were caught in a storm, and those who were navigating realised that they no longer knew where they were. After three nights at sea, on 23 June 1982, all onboard were safely rescued in the South China Sea by Le Goëlo. The boat rescued became known as the 101 Boat because there were 101 people on board. Le Goëlo was on a humanitarian mission, chartered by the French group Médecins du Monde. (Bernard Kouchner, the founder of Médecins Sans Frontières, broke away to establish MdM with the objective of rescuing Vietnamese refugees at sea.) MdM’s rescue of the 101 Boat on Le Goëlo was filmed and publicly profiled to aid emerging oceanic humanitarianism.

Survivors of the 101 Boat gather annually in Paris, where many were resettled, to commemorate their rescue through a memorial service and Catholic mass. They do not only focus on their own journey or escape, but that of other boat refugees, particularly remembering those who drowned. Anh attended this event in 2019 as a member of the community, and carried out oral histories with the adults who planned the escape.

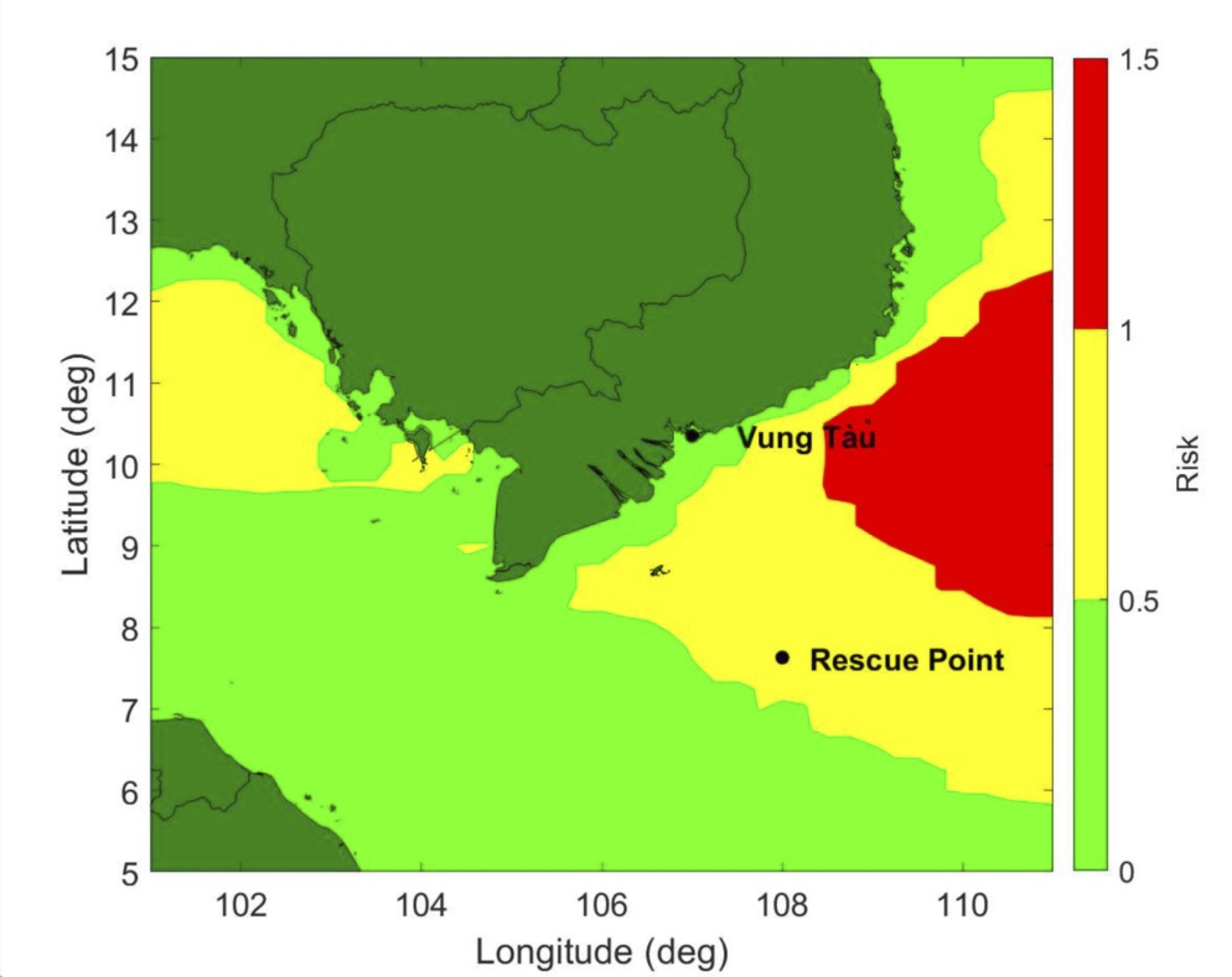

This map was created by ocean engineers using the ERA5 database of historical global estimates of marine conditions. It represents the relative danger that the ocean and weather conditions posed for the refugee boat after it departed Vũng Tàu, a town on a peninsula of southern Vietnam, on the morning of 20 June 1982. The map depicts the South China Sea and the southern part of Vietnam, showing the place of departure for the vessel and where it was rescued. Risk was calculated by combining key motion of the vessel in terms of heave (movement of the vessel up and down in the water), pitch (see-saw type movement of the vessel from front to back) and roll (tilting movement side to side). Areas in green are low risk, yellow is medium risk and red is high risk.

From the engineering analysis, it was concluded that the weather during the journey was extreme, and dangerous for a vessel of the size of the 101 Boat. The wave heights at the centre of the storm (the red region on the map above) were ones that could be expected once a century. The environmental forces were greater than the power of the boat, and these conditions determined the final part of the route that the boat took. The people aboard the boat had intended to go to the Philippines, but the wind and waves pushed it around the edge of the storm, where they were rescued (in the yellow region on the map showing an area of moderate risk for a vessel of this size). Weather conditions were also part of the memories of survivors interviewed, but their explanatory narrative focused on their belief in God. As Catholics, they understand their safe passage as an act of God, because the ocean is understood to be within God’s command.

In examining both oral histories and scientific analysis, we are not seeking to privilege either of these means of representing and understanding the experiences of Vietnamese boat refugees, but seeking to think about how we can work collaboratively and across disciplines. This enables us to explore historical data estimates as new bodies of evidence to incorporate into historical analysis. In this case, we focused attention on the ocean as an active and multi-dimensional agent, that both made a refugee boat journey perilous but created conditions which facilitated the boat’s rescue. Doing this made the distinct role of the ocean in this journey visible in new ways.

The header image shows a satellite map of the South China Sea from the coast of Vietnam to the Philippines.