Writing the personal: when history is your family story

On 4 August 1972, the president of Uganda declared his intention to expel the country’s South Asian population. The exodus that followed saw up to 80,000 people being given 90 days to leave their entire lives behind. This seismic moment sent shockwaves through East Africa, Britain and beyond – as well as through my family.

Having been recruited in southern India by a British scout during their first year of marriage in 1953, my grandparents had spent close to two decades teaching in Uganda. They, along with their three children, including my mother, would go on to the UK and later Australia.

I don’t know when I first heard of Idi Amin. But I would tell children in the school playground how my family were forced to leave a country called Uganda because of a man called Amin. Forced migration was incongruous with both my suburban Sydney setting and my youthful innocence, but it was part of my DNA and something I asked questions about, even as a five-year-old.

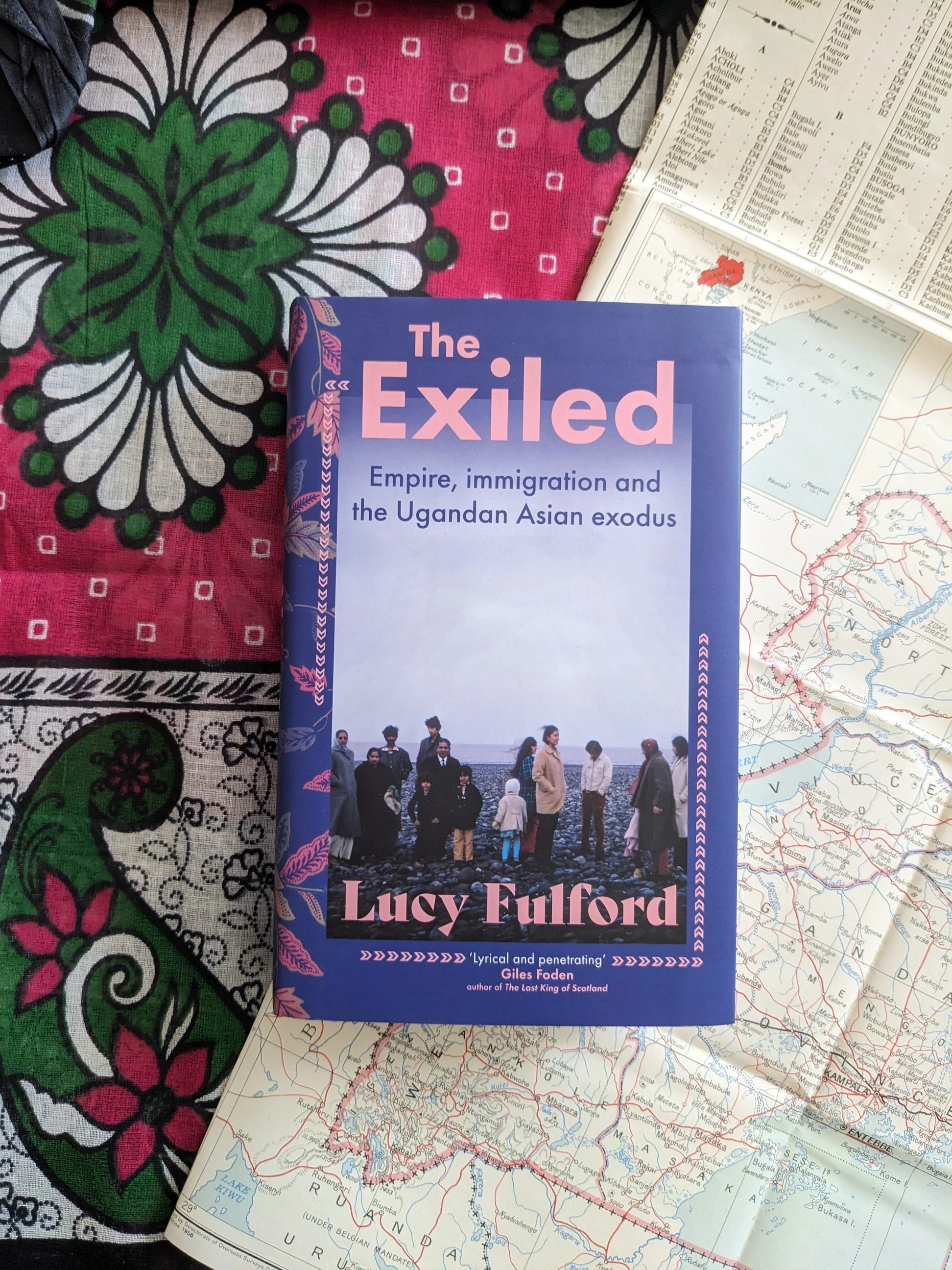

Many years later, I started asking those questions more seriously, in a work that became my book, The Exiled: Empire, Immigration and the Ugandan Asian Exodus. As the 50th anniversary of this landmark migration approached, I was increasingly frustrated by the simplistic narratives around victimhood and wealth, success and the trope of the ‘good migrant’ that I saw spun around Ugandan Asian stories. I wanted to challenge the problematic ways this history has been politicised, and show how colonial legacies continue to reverberate down the generations.

* * *

My family in Kampala in 1970s before leaving (grandparents, aunt and uncle). Courtesy of Lucy Fulford.

For the first time, instead of telling other people’s stories, I was exploring my own. Tackling a subject that was intrinsic to my existence forced me to examine the idea of objectivity, and constantly challenge my own perspective on the material. It would take me longer to appreciate the distinct advantages of understanding something in a bone deep way.

Not only was I covering a story that was close to me, I was placing myself within the narrative. On the recommendation of beta readers and editors, my family’s migratory journey would be woven amongst interviews and archival research, from my grandparents’ wedding vows in the Keralan hills to my reflections on growing up as a child of multiple continents.

Writing something this personal didn’t come naturally to me, but I could see that many of my favourite reads tied an author’s voice with a wider history and historiography. My main motivation had been to bring a lesser-known history out of academia and onto popular shelves, and I knew that it often fell to those with a personal connection to the past to champion underexplored, minority histories.

* * *

One of the first challenges I faced in writing the personal was around selectivity. As researchers and writers, our work comprises a constant series of choices. Incorporating a familial link, however, added a layer of complexity, and second-guessing. Was I being fair, or was I subconsciously gravitating towards certain voices? Was I showing someone in a better light than they deserved, or self-censoring?

These are valid questions to ask ourselves whatever we are researching, and having been rigorous with myself on this project has strengthened my approach more widely. I attempted to fight any in-built bias or favouritism by auditing myself on how representative my work was, whether from ensuring all the major religions represented so markedly on the Kampala skyline featured, through to speaking to people of different socio-economic statuses, from different regions of India and different professions. With representation in mind, I also worked hard to create a gender balance in my source material, seeking out previously overlooked female voices.

Having an intimate connection to some of the histories I was telling meant I was at times caught in a battle between the appeal of a good story and the sensitivities of family privacy. I worked hard to respect the wishes of loved ones, or of anyone who asked to remain anonymous, and leaned on alternative sources to fill the gaps, rather than leave them empty.

There was always the risk that my interests would be piqued by particular things which had intrigued me over the years, rather than those which propelled the broader narrative. Writing the personal means risking writing what you’re interested in, as you have a harder job in being dispassionate. You can find yourself getting lost in the detail, because you know so much of it without setting foot in an archive.

* * *

I came to realise that what I sometimes perceived as weaknesses were simply a part of the methodology of family history, and that my positionality added immense value. The details became vivid colour or allowed me to ask questions I wouldn’t have the means to when researching something new to me. I had grown up with snatches of Swahili and Malayalam that I could ask about or use to infuse my manuscript with the sounds of Kampala. Having this as lived experience within relatives’ memories meant that I could go deeper, gaining context or clarity outside of interview settings and before wading through resources.

In the pursuit of telling a social history of the expulsion, I wanted to shine a light on the lesser-heard voices, moving beyond affluent businessmen to everyday experiences of exile. Most people I spoke to for The Exiled had never been interviewed before, shared their memories widely outside of their families or ever thought they would be considered part of ‘history’. The shame and stigma of struggle, coupled with the migratory desire to speak to the better times, meant some things had barely been discussed within families either.

Doors opened to me in ways I had never experienced before. Sometimes I barely had to get past the words, ‘My grandparents left in 1972,’ before I was welcomed into homes, shops, or conversations. While I often didn’t share much of a background beyond the Uganda connection – coming from a Keralan Christian family who spoke Malayalam set me outside of the dominant Gujarati or Punjabi communities who emigrated to East Africa – that common ground was enough to build trust. Interviewees opened up, sometimes startlingly quickly, sharing deeply personal memories of trauma, racism and loneliness.

Matching old with new, visiting my family's former Kampala house 1972 versus 2022. Courtesy of Lucy Fulford.

I led with my heart and, unlike usual interviews, shared my own stories too, building a natural conversation. Having the ability to add a personal anecdote to validate an interviewee’s experience, or to confirm a location or time marker really strengthened the work. I have been moved at the connections I have built and original stories I have heard.

For many years I actively avoided writing about Uganda, fearful of being typecast as a Brown woman writing on race. But as the years passed, I saw how certain histories fell through the cracks until they were taken on by someone who felt their importance every day, rather than solely through a news agenda. When the shelves remain dominated by the same kinds of books, we shouldn’t be afraid of touching on the things that sit close to us, whether through personal connection, or niche interest. This could in fact be our greatest strength. The Ugandan Asian story is a living history, and one which I am honoured to have given life to on the page.

The Exiled: Empire, Immigration and the Ugandan Asian Exodus (Coronet, Hachette, August 2023) is available in hardback, e-book and audiobook now. https://www.hachette.co.uk/titles/lucy-fulford/the-exiled/9781399711173/

This post is based on the experiences of writing this book, as well as supporting journalism, including The Guardian’s Moment That Changed Me column: 50 years after my grandparents were expelled from Uganda, I visited their old home