Refugee aid in eighteenth century Sweden, Part II: boundaries of responsibility, limits of compassion

This is the second part of a Refugee History blog based on ongoing research within the project Humanitarian Great Power? The local reception of refugees in Sweden 1700-1730, funded by the Swedish research council. Read the first part here [LINK].

“[T]hat I, wretched and poor widow, have to sate myself each day with sighs and tears in the greatest misery, knowing of no meals for myself than crying and wailing, had not God inspired Christian people to take pity with my sorry state. But since all [people] have their own difficulties in this sorry war, they tire of [providing aid], as the number of exiles increases daily.”

This is how Gunilla Nilsdotter, in a petition addressed to the Swedish king, described her situation as a refugee in Stockholm in the 1710s. Her words speak to the importance of private acts of charity and compassion for refugees’ survival, while also expressing how this compassion was by no means limitless.

The first part of this series explored the emerging discourse on refugee protection in eighteenth century Sweden and the efforts of the Swedish crown to assist wartime refugees fleeing occupied eastern provinces of the realm during the great northern war. This second part investigates the reception of these refugees on the local level.

Notions of humanitarian responsibility are intimately linked with the boundaries of community, defining the reach of solidarity and compassion. The disintegrating Swedish Empire was a conglomerate of loosely interconnected regions, and while refugees from Finland and the Baltic provinces were Swedish subjects, they were strangers in their receiving communities. This raises the question: how far was the Swedish host population willing to extend their compassion towards refugees from the provinces when the state’s capacity to provide aid proved insufficient?

The geographical scope of responsibility

The diocese of Härnösand, located on the periphery of the Swedish empire in the north of modern-day Sweden, was poor and thinly populated, but between 1713–1721 the region received approximately 40% of the 20,000-30,000 refugees fleeing the occupied Swedish provinces. This situation led local authorities, such as the bishop and royal governors, to challenge the centralised, state-organised refugee aid, arguing that the relief effort coordinated from the imperial capital was incapable of effectively responding to the locally unfolding refugee crisis. The diocese, they claimed, must be allowed to take care itself of the refugees settled in the region. Ultimately the king agreed, allowing the diocese to create its own regional relief organisation independent of the national relief efforts.

The town of Härnösand served as a major hub of refugee migration. Source: The Royal Library of Sweden.

As the cathedral chapter of Härnösand began coordinating refugee aid in the diocese, however, a similar debate to that which had played out on the national level now took place regionally. The bishop and the chapter advocated centralised control over the collection and distribution of aid in the diocese. Considering the uneven distribution of wealth between parishes and the equally uneven distribution of refugees, the cathedral chapter wanted to pool all charitable donations form the diocese and redistribute the money to the parishes, to ensure that each refugee received a fair share of the collected funds. Many vicars, by contrast, wanted to distribute charitable donations locally. Welfare institutions were, by tradition, local in scope, and parishioners therefore expected to see the effects of their charity. Vicars and parishioners perceived their responsibility as lying towards vulnerable migrants in their own community, not anonymous refugees from the empire writ large.

The debate persisted throughout the war, as the cathedral chapter struggled to strike a delicate balance: decentralising the distribution of aid tended to yield better fundraising results, but also resulted in growing inequality between parishes and refugees.

Compassion vs local self-interest

When refugees from the provinces arrived in Sweden, the local community perceived them as temporary aid seekers who would return home as soon as the war was over. However, the Great Northern War continued for more than two decades and as time passed, compassion fatigue set in among previously enthusiastic donors. While initial fundraising campaigns were relatively successful, results dwindled alarmingly over time, even as the number of refugees increased.

Cathedral chapter minutes and court records suggest that the resident population increasingly wanted to put clear limits on their economic responsibility towards the refugees, who were constantly going door-to-door in the villages begging for alms. In January 1721, the vicars of the diocese unanimously proposed to the bishop that they replace the system of fundraising with a fixed annual contribution from each parish; in return, the authorities would enforce a ban on begging. This proposal was intended to limit the parishes’ responsibilities by redirecting the refugees to official – though inadequate – channels for aid. This in turn was partly driven by developments in the war, which now directly affected the region itself. From occupied Finland, Russian raiding parties were launching raids on mainland Sweden, sacking and destroying towns and villages in the northern regions of the diocese as well as along the Baltic coast. These raids disrupted the local economy and created new victims of war among the resident population.

With the economic situation in the region deteriorating, it became increasingly difficult for the authorities to legitimize refugee aid, as the host population began to prioritise defending narrowly-defined local interests. When the town of Härnösand had received a large influx of refugees following the Russian conquest of Finland in 1715, the townspeople had spontaneously opened their homes to the refugees, in clear violation of municipal residency restrictions. Two years later, this early hospitality had become increasingly strained, with as town council minutes testifying to the locals’ growing frustration with refugees who violated the town’s trade regulations. Similarly, the cathedral chapter had initially offered employment to refugee pastors from the provinces, but in 1720 it ceased such charity work, declaring that “for too long have the noblest parishes been staffed with strangers, by which the natives have come to suffer, since the diocese on its own is so crowded that it cannot support its own students.”

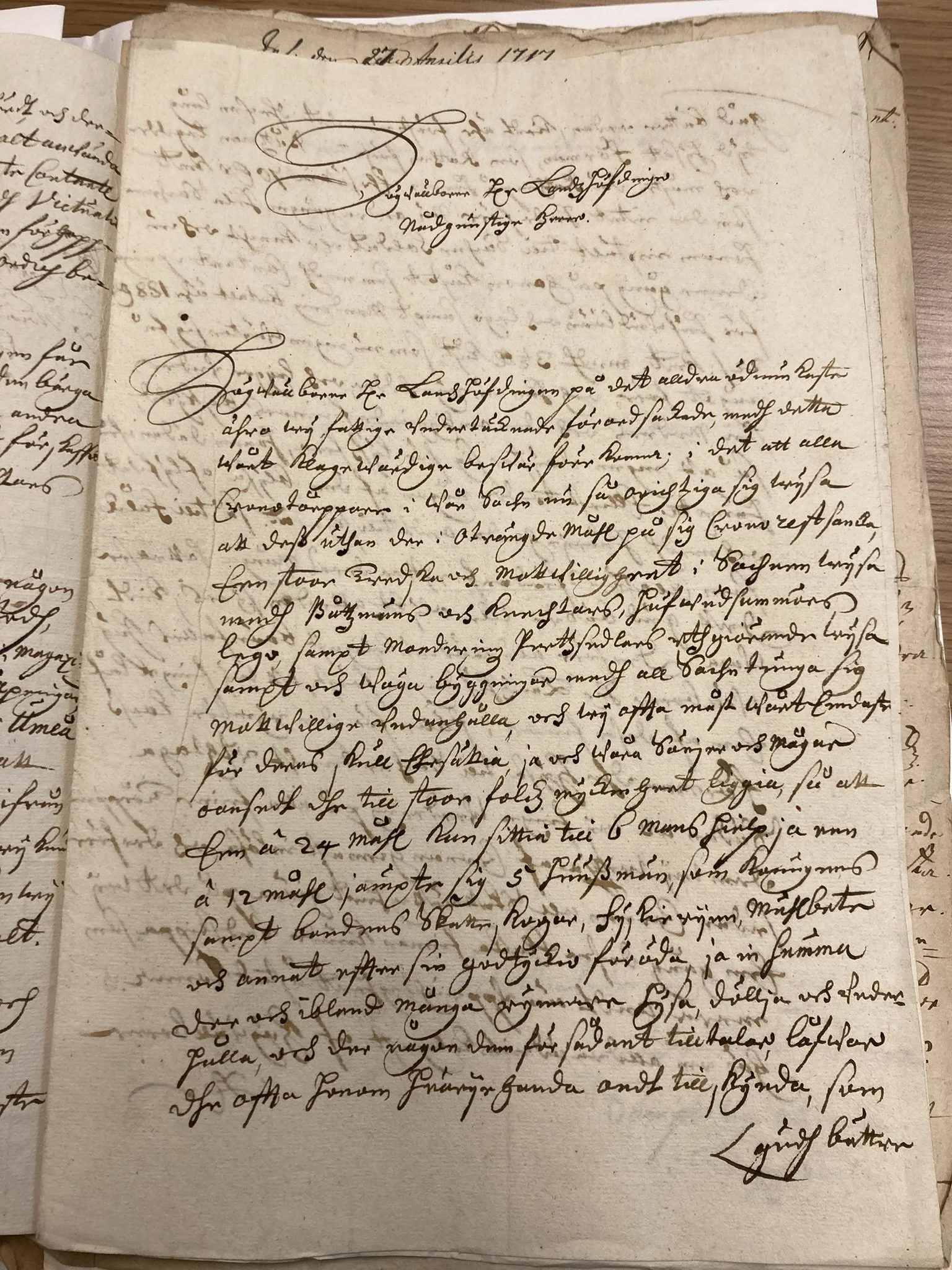

A particularly striking account of increasing hostility towards refugees comes from the rural parish of Torp, suggesting ethnic conflicts between the resident Swedish-speaking population and Finnish-speaking refugees. In a petition to the royal regional governor, the parishioners recounted how the Finnish refugees lived in their own community, physically separated from the village, and described their duplicitous and hostile attitude towards the locals. As these refugees were settled on royal land, the parishioners offered to buy the property and accept all the associated tax duties in order to evict the “evil Finns” from the parish.

Petition from the parish of Torp to evict refugees from the community. Source: The Swedish National Archive (author’s photo)

Refugee aid and the boundaries of community

The reception of refugees in the diocese of Härnösand reveals how attempts to ensure a fair distribution of aid among the needy had to be weighed against the need to legitimise relief efforts among donors. While the authorities strived to centralise relief efforts in order to ensure that aid reached the refugees most in need, local donors wanted to help the refugees closest to their own community. All too familiar to modern humanitarian debates, this tension underlines the prevailing challenge of how to expand boundaries of community and scope of solidarity.

Initially, the locals of Härnösand were ready to extend their compassion to the refugees, as fellow imperial subjects in need. Over time, however, as the region came under increasing pressure, the self-interest of the local community trumped the community of Empire. Rather than vulnerable migrants, deserving of protection and compassion, the locals came to identify refugees as threats to the welfare and security of their community. In eighteenth century Sweden, the realm as an imagined community was clearly subordinate to local and regional forms of community, and solidarity with fellow subjects of the realm by no means guaranteed.